🫗 Far from clear: Does glass beat plastic?

We compare the two materials from an environmental and EPR perspective

If there is one thing we learn over and over at FTF HQ, it’s that there is no simple answer in sustainability. That doesn’t stop us hearing, and asking ourselves, the simple questions. We want to know: If we want to do the best by the planet, should we use glass or plastic packaging?

Today Indira will help us unpack that and generously shares her own (very informed) opinion on the matter.

> In Focus

Plastic vs. Glass Packaging: Material and Environmental Comparison

Let’s dive into the current heated debate on packaging: is plastic or glass the most suitable material in terms of sustainability, considering its weight and recyclability? What are the opportunities for glass, now that it has to pay higher overall EPR costs despite having a lower EPR price per tonne?

As a reminder: Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) is a policy approach designed to add the environmental and management cost of processing product waste into the product’s lifecycle, mainly by putting that cost on the producers.

As an advocate of reusable packaging, my preference will become pretty clear at the end. Of course, the ideal scenario is that we have the right infrastructure to support it, but we know it won't be an easy journey to get there. As you read, the suitability of both materials will always depend on the purpose as well as the existing infrastructure available to treat them, so there may be occasions when one material is better suited than the other.

First, let’s break down the differences between plastic and glass as materials

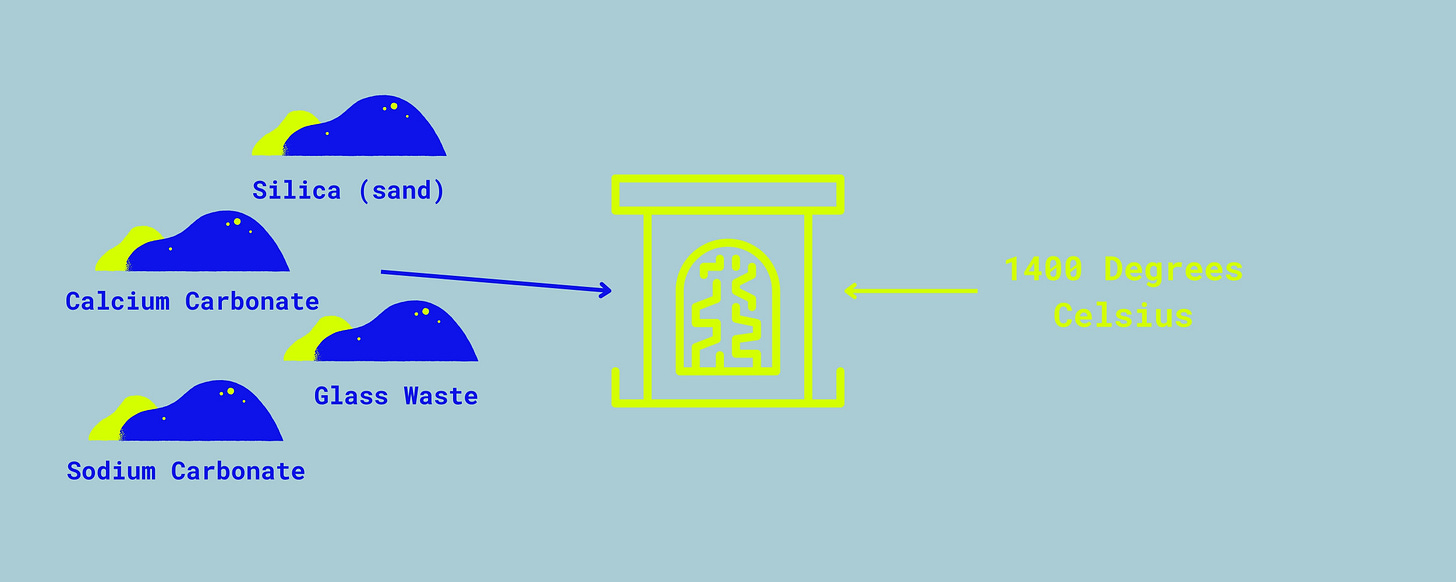

Glass is mainly made of silica, which is a natural substance (silica dioxide makes up 59% of the Earth’s crust) that is less likely to cause pollution compared to plastic. However, glass production requires very high temperatures, leading to higher CO2 emissions released during its manufacturing, which can be up to eight times more than those of plastic.

Glass is also referred to as a material that can be infinitely recycled, as the glass cullets can be melted down and used to produce more glass. The average glass recycling rate is 76% compared to 41% for plastic packaging. Similarly to the emissions produced during its production, the recycling of glass is also energy-intensive, as remelting glass to glass cullets requires high temperatures.

On the other hand, plastic is a material derived from natural gas, oil and coal. Plastics are made synthetically, meaning they are manufactured using chemicals. Molecules are chemically linked to form long chains known as polymers. The melting point of plastic depends on the type of plastic being used, but it is generally much lower compared to glass. They are also robust and can be used for a long time, and are lighter than glass, which leads to better fuel efficiency during transport. These reasons make plastic a more appealing material of choice for packaging.

Plastics are often linked with being easily recycled and that we have many recycling facilities for plastic. However, plastics can only be recycled once or twice, each time losing its structure, so they are downcycled into other materials. Only 9.5% of products are recovered for recycling, and we still face many issues with plastic being mismanaged, taking hundreds of years to decompose and releasing microplastics.

This then prompted brands and producers to use glass packaging for environmental reasons. Yet, economic pressure from regulations like the pEPR is increasing.

The impact of EPR

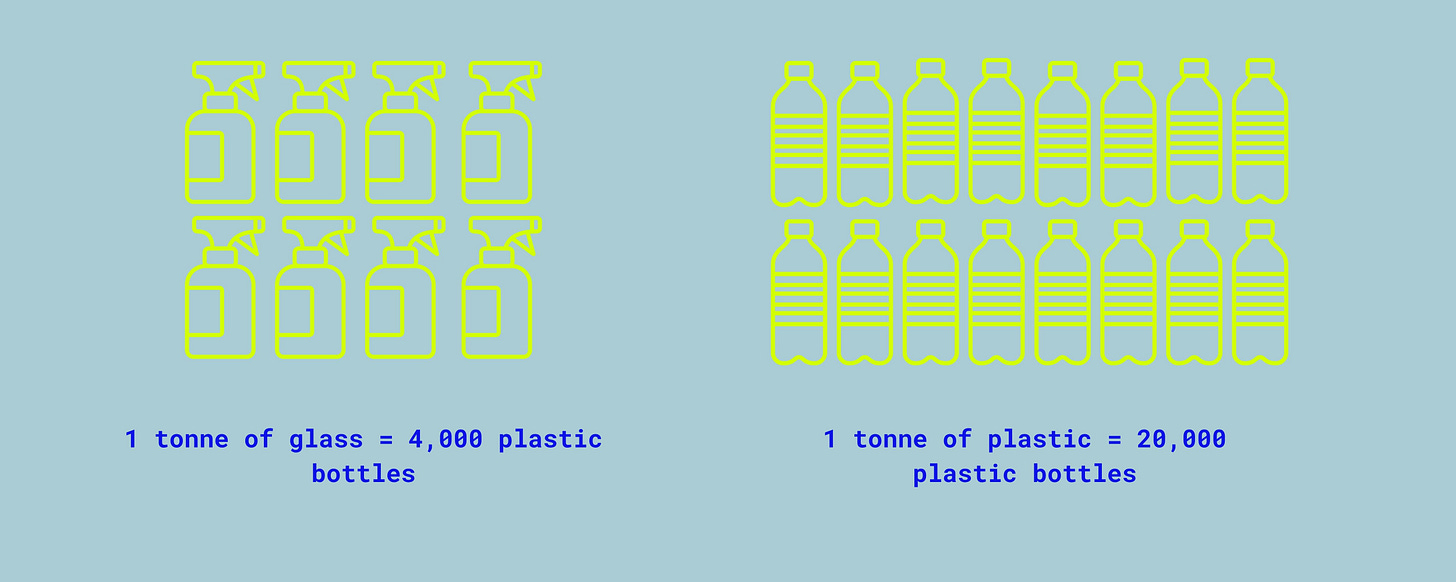

Packaging Extended Producer Responsibility (pEPR) regulations aim to shift the financial burden of packaging waste management from local councils to producers. The fees are typically based on factors such as material type, recyclability, and especially weight, an approach that has direct implications for the glass vs. plastic comparison.

With the UK’s latest EPR scheme update just a couple of days ago, glass packaging will face a base fee of £192 per tonne, compared to £423 per tonne for plastic. At first glance, this suggests that plastic is more expensive. However, for the same volume and dimension, a plastic bottle may weigh only a few grams, whereas a glass bottle weighs hundreds of grams. This means producers that use glass will end up paying higher overall EPR costs.

Unfortunately, this can lead producers to revert to lighter, cheaper packaging. Plastic still remains the primary material for packaging despite the impacts discussed above. Some glass bottles used for beverages are considering switching to paper bottles. Returning to the caveat about the best material depending on its purpose, these alternatives often have limitations, as paper tends to absorb moisture and requires inner linings of plastic or foil, making them harder to recycle and unsuitable for long-term storage of liquids.

This, in theory, can lower their EPR fees due to the paper; however, with the ecomodulation rating of fees (adjusting fees based on the environmental impact of packaging), which will also be assessed based on their recyclability, it could then become more expensive. Even without the fees, the additional linings and configuration of the paper bottle innovation can potentially hinder the recycling process, making the packaging unrecyclable and therefore failing to meet environmental goals.

This is an opportunity for glass to step up the waste hierarchy chain, to reuse, as a long-term advantage.

The importance of context

The issue related to these materials often does not stem from the material itself, but rather from consumer behaviour that is so conveniently reliant on single-use items. Plastics are initially introduced because of their long-term durability but have been treated in a single-use manner, polluting the environment. But the way we have been using it is what is causing the problem.

Considering the emissions produced during the manufacturing of glass, which is designed to be durable enough for multiple reuse cycles, this presents an opportunity for glass to be reused to offset its initial energy and carbon footprint. Refillable and reuse systems (such as returnable beer bottles) allow a single glass container to be used repeatedly, significantly decreasing the environmental impact per use. Additionally, glass can often be largely exempt from EPR burden once it enters a documented reuse cycle, providing a strong financial incentive to invest in return systems and durable packaging design. Over time, this results in a cost advantage for glass that grows with each reuse, making it not just more sustainable but also more economically competitive in the long term.

Plastic, on the other hand, is not really designed for reuse. With each use or exposure to heat, plastic can degrade, releasing microplastics and chemical residues. While plastic may currently offer short-term savings, in the long run, the impacts will become more visible, making it more costly to use this material later on as the initially unseen effects start to emerge. Regulations shift to prioritise reusability and carbon accounting, and plastic-heavy brands will eventually face higher costs and limited compliance options; they will inevitably need to transition to more sustainable circular materials.

In conclusion…

The key criterion for packaging material is clear: it should be designed for reuse and made from durable materials. But as I hinted at the start, it depends on the specific application and purpose. You might consider biodegradable materials next, but is it truly sustainable given that we lack the necessary infrastructure to handle its end-of-life? Ah, another story for another time!

It’s a lot to consider, and the issue is still evolving. If you are a brand deciding between using plastic, glass, or other materials and would like to share your thoughts with us, please feel free to do so!

> Finally, in case you missed it…

Want more? Check out our Website! You can find more about the team behind this newsletter, dig through our content archive AND check out our handy databases there too.

Have ideas for what we should write about next? Reply to this email! We’re always looking for inspiration from folks like you.

Until next time!

Team FTF

I think another point you touched on was the studies around microplastics in our bodies, the sea etc and the effects on fertility and other health problems.